Ami Skånberg Dahlstedt’s reflections from Ricklundgården in Saxnäs, northern Sweden/Sápmi

Dear reader,

this post will be in English. It is a text I started to write in February at Ricklundgården , while I was preparing for Nordic Summer University‘s winter symposium held in Sápmi/northern Sweden for the very first time. Now I am back again to do some more work on texts and video. I think it is time to finish this text and finally publish it.

This is how the sky looks just now, Dec 30th 2017:

Marsfjäll in moonlight. View from Ricklundgården. Photo: Palle Dahlstedt

Marsfjäll with northern lights and meteorite on Chrismas Eve 2017 Photo: Palle Dahlstedt

Where are we? We are at Ricklundgården in Saxnäs, a home built by Emma (1897-1965) and Folke Ricklund (1900-1986) in the 1940s. Emma, originally from Saxnäs, was working at her parent’s inn in Saxnäs, when she met the artist Folke who came here to study and learn about reindeer hearding with the Sámi people. Emma and Folke were both art and nature lovers and together built this very special house in Saxnäs. After they divorced, Emma and her Sámi collaborator Lisa Stämp kept the house open for visiting artists. My connections to this place is related to the wonderful opportunity of an artistic residency that people from all artistic fields can apply for. Also, my husband Palle Dahlstedt has his roots here, and we spend each summer in this area.

First of all I would like to thank the chairwoman of the board of Ricklundgården, Gerd Sjöblom Ulander, who is also a fantastic teacher, singer and voice artist. Gerd is always so helpful, and there is nothing too difficult for her to solve. Not only did she open up Emma Ricklund’s home for the NSU Circle 7 winter symposium, but she also offered artistic residencies to four of the NSU Circle 7 artists.

Gerd Ulander in Folke Ricklund’s atelier at Ricklundgården, 2016

This is the first time when the Nordic Summer University organizes a symposium in Sápmi. The study circle 7 consist of artists and artistic researchers from many different fields. There is an ongoing discussion about what ‘Nordic’ really means. The term ‘Nordic’ has been used as an ideological and commercial construction in which not everyone has been included. I myself grew up believing that in Sweden we are all equal, every man is a feminist, and that all social classes have been erased. I was certainly not alone believing that this was the case. Sweden has been marketed as the social democratic paradise where each and everyone is included. My co-coordinator Lucy Lyons and I hoped that by being here we would think further about place, heritage and privilege, and bring these thoughts into our future work.

Ami Skånberg Dahlstedt and Lucy Lyons in Riga, 2016

Ricklundgården

When Emma Ricklund wrote in her will that she wanted her home to remain a residency for artists, maybe she also found a solution to the dilemma of museums as a place for preservation of objects and of memory, where the risk always is that the past cannot communicate with the future. By inviting contemporary artists to work in her home, artists might become the agents for change, for exchange, for creating a link with the legacy of the museum itself, and with the legacy of the local environment.

Emma Ricklund

When we stand in the middle of Folke Ricklund’s atelier, maybe the atelier itself could be seen as a monument of the Artist, the male genius in a big room with a view, depicting Marsfjällen on canvas. However, Gerd informs me that Folke always preferred to paint outdoors. Today artists come to Ricklundgården to make videos, to read, to write, to formulate a research question, and to dance. Thus the visiting arists constantly change how this place was practiced in the past.

Sápmi

Ricklundgården was built in northern Sweden, and thus also in Sápmi, but Sápmi is not a national state. There are about 20.000-40.000 Sámi people in Sweden. It could be as much as 50.000 persons, but nobody knows exactly how many who identify themselves as Sámi. Out of these, 4.677 persons are caretakers of the reindeer. In Norway there are about 50.000 – 65.000 Sámi people, in Finland about 8.000, in Russia about 2.000. Not until 1977 did the Swedish Parliament pronounce that the Sámi people are an indigenous people in Sweden, even though the Sámi have been here for thousands of years. In 2000, there was a new minority language law for Sweden’s five national minorities, where the Sámi language was recognized at last. And finally in 2011, the Sámi people was recognized as ‘a people’ by the Swedish constitution. This recognition of being pronounced ‘a people’ additionally means legal protection. Sweden has finally recognized that the Sámi are a people, an indigenous people and a minority.

Today we start to be aware how “voyages of discovery” were in fact voyages of invasion. One example of these voyages of invasion in the Scandinavian countries is the colonization of Sápmi, in Sweden called Lapland. Sápmi was seen as ‘the space out there’, and a lot of effort was being made to create a national place out of this ‘unknown’ abstract space. In this case it also meant a Christian place, where everyone must speak the same language, give up ‘pagan’ singing and dancing, and pray to the same God – ‘real’ and valued practices. Adding on to that, during the 18th century, Sweden’s central government’s debt grew and inflation was high. The northern part of Sweden is rich with resources, and the government decided upon the building of ore mines as a way to pay some of the depts. This is when the forced recruitment and the oppression of the Sámi people began.

The young Sámi generations are at this very moment reclaiming their own history by relearning the Sámi language and the crafts once forbidden by the non-secular Swedish state. Some are looking for ways to continue reindeer herding and to make a living without having to move to bigger cities. Tourism is one solution, but with it comes issues on how space is practiced and performed. When indigenous people struggle to make a living in a space invaded by colonialists, and decades later are asked to perform an authentic illusion of the past, it often leads to a commercial construction of space. The new generations’ reclaim consists of different alternatives and practices for change, i.e. to make a new context out of space-specific ‘old’ practices. This is visible in the contemporary arts practices by Sámi artists such as Katarina Pirak Sikku, Hilde Skancke Pedersen, Tanja Andersson, Ola Stinnerbom, Saara Hermansson, Silje Figenschou Thoresen, and Amanda Kernell.

Saara Hermansson, Västra Stornäs

Contemporary Sámi artists

I will share how some contemporary Sámi artists have reflected artistically on the environment, on heritage and legacy. This is Hilde Skancke Pedersen next to her art work that she created for the Sámi Parliament:

We screened her art film EANA (Sámi for “land”) at the winter symposium. Hilde works in various materials, and is also involved in cultural politics. She lives in northern Norway/Sápmi, and she is a representative at the Sámi Artist Council. She presents her work with the film here:

‘In the film EANA a naked, female body mirrors the shapes of the landscape in the Sámi hinterland. The film addresses the similarities between an ageing body and the rugged mountains, and the close bond between humans and nature. The Sámi culture is closely connected to nature, and the fight to preserve Sámi areas from exploitation is ongoing. This struggle is supported by a majority of the Sámi population, while feminists and homosexuals still suffer from prejudice. In some Sámi communities, the church does not employ female vicars. In Sámi society, privacy and a strict bashfulness has ruled since the Christian religion took hold in the 18th Century. The traditional way of dressing, strictly covering the body, is still in daily use among many elderly people, and is often used by all ages for festivities. In contrast, many young women are scantly dressed for evenings out, in accordance with current fashion, often dancing to Sámi rap music with explicit sexist lyrics. Until recently, the Sámi female body was accepted regardless of size, shape and age. My aim is to research the paradigm shift in this field.’

Silje Figenschou Thoresen

Silje Figenschou Thoresen is trained in contemporary art at Scandinavian art schools. She works conceptually as a Sámi person, and she is using Sámi inventions for contemporary art – a decolonial maneuvre to be able to eat and keep the cake. She argues herself that she is taking Sámi art and moving it into contemporaneity. Her fundamental ethos is the respect for nature, and not to let anything go to waste. Sámi-self-sufficiency, utility projects and the self-reliance of a people with limited resources and an inherent DIY- mentality are the starting point in her work. These are her sculptures:

The artist Katarina Pirak Sikku really tried to come and present her work at the NSU Circle 7 winter symposium in Saxnäs. She had just received her first research grant from the Swedish Research Council, and would have loved to replace her small workspace in Uppsala to Saxnäs. She has had residencies at Ricklundgården before. Her family is from this area. In Katarina’s artistic practice, she is processing dark Swedish history. She has been looking for her own mental independence, and finally decided to start to work with rasbiologi, in English racial biology or eugenics.

Katarina Pirak Sikku with tools for craniometry

In 1922, the National Institute of Racial Biology was established in Uppsala in order to document the Swedish population. Herman Lundborg was the leader of this institute until 1935, and he was particularly interested in people of northern Sweden, where a large part of the population was a mixture of the Sámi, Swedes and Finns. Herman Lundborg looked for evidence that ‘racial mixtures’ had bad consequences. Before he became a professional racist, he was the head of the women’s department at the psychiatric clinic in Uppsala. His writings had a huge impact, and he had a big readership outside the traditional science field. Besides writing, he traveled around and measured and photographed both children and adults while exhibiting ‘racial types’ and different kinds of people’s typical appearances, which survived in people’s minds long after his death. The notion that the Swedish race was being degenerated, and that this must be combated resulted among others the introduction of sterilization law in 1934 (not abolished until 1976). The National Institute of Racial Biology remained until 1958, and Lundborg’s methods was being implemented and used by the Nazi during Second World War. During these dark twenty-three years this institute caused great harm to a lot of people.

Katarina Pirak Sikku looked through the archives, where she found endless photos of Sámi people without names. She looked at Sámi handicraft, and there were no names of the craftsmen. She found a bag that her grandmother had made, and she wondered if she should be grateful that someone had preserved it and put it in a museum? She could not be grateful, she did not want to be grateful. She found it very difficult to work with these photos, and during the work she realized that her intention was not to write the history of racial biology in Sweden. Instead, she wanted to talk to people, and to find someone who might remember what had happened during this time. She also wanted to find out how it felt to be measured. She started to take pictures of herself with the original measurement tools that she borrowed from the archives.

Katarina Pirak Sikku also wanted to look at the Sámi self-image. But how? She was not sure. Shouldn’t she start to photograph Swedish people instead, posing with cows – in order to show the absurdity of depicting people in ‘authentic’ ways? Katarina loves the Sámi handicraft, for example the embroidering with the tin thread on broadcloth. She also loves the fact that there are so many strict handicraft rules. At the same time, she was also very upset with the Sámi handicraft, and with the many rules. She decided to make a provocation, something to upset everyone. Katarina worked with pearl embroidery, and created a Sámi bikini and took a photo of herself. She felt that some of her anger disappeared after she took the photo, and that it helped changing her self-image. Katarina thought that this photo helped her to think of a contemporary identity, a different self-image.

Saara Hermansson, a young Sámi activist from Västra Stornäs, also talks about the self-image and what happens when you try to find something that has been lost. Can she use old Sámi patterns in her embroidery, even if they are not clearly from her own family? She mentioned the word ‘koltpolis’ in her speech. A ‘koltpolis’ (frock police) is a person from the Sámi community who acts like a police in an attempt to control the authenticity of the Sámi clothing during informal and formal gatherings, festivals and markets. Saara also talks about identity and jojk, please see an excerpt of her speech at Ricklundgården here:

Just before the symposium started, a new film by the Sámi film director Amanda Kernell premiered in Sweden, called Sámi Blood. I watched it in Vilhelmina together with Saara Herrmansson. Like Katarina Pirak Sikku, Amanda Kernell is dealing with the ‘forgotten’ or actually repressed history on how Sámi people were treated in the 1930:s in Sweden with a focus on Nomad schools (lávvu schools). Nomad schools were invented for the children of reindeer farmers. They could not go to the same schools as Swedish children or as Sámi children without reindeers. The pupils often had to stay in badly insulated goahti (Sámi huts), since the idea was that if they stayed in houses they would become like Swedes. In these schools and in the Swedish schools, the Sámi children were forced to speak Swedish and not allowed to speak their native language. The film shows how Lundborg’s fake research on racial biology was implemented. Children were divided based on ethnicity and family background, which caused the fragmentation of the Sámi culture that we see today. The film follows Elle Marja, a 14-year-old reindeer-breeding Sámi girl. Exposed to the racism of the 1930’s and the race biology examinations at her boarding school, she starts to dream of another life. Watch the trailer here:

In SILVERFEBER (Silver fever), the choreographer Tanja Andersson was probing colonial traces in the physical body and scattered identity. Silver fever takes off in the 17th century in Northern Sweden – Sápmi, when silver was found in the area of Nasafjäll. Subjugation and enslaving of Sami people initiated by the state of Sweden began. A variation of the torture method Keelhauling was practiced on the ones who refused work. Tanja is looking for a social and cultural inheritance, silenced for such a long time. How will experiences unfold in the passing down from generation to generation? In what ways will it be expressed corporeally? How does it affect movement?

Tanja Andersson and Emelié Sterner in Silver fever 2017

There is something in my blood. It rivers around, impossible to divide. Felt like undercurrent in white-water but it is my old man, it is you. It might be grandpa when he fell through the ice and came back, or it could be the uncles – those who lingered beneath the streaming surface. It must be the women, tough and hard-baked, for now we slowly lift our chins. I hear the sound of joik but I can’t sing along. Never learned the language since they hit you ‘til you stopped talking. A tremor in the torso with bones longing to fracture. A man borrows my vocal chords before he, with tightly bound wrists, is dragged into the freezing cold water.

In Swedish:

Det rusar runt, runt och går inte att sortera. Trodde det var underströmmar i forsen men det är farsan, det är du. Det kan vara farfar när han gick igenom isen och kom tillbaks eller kanske farbröderna – de som stannade kvar under vattenytan. Det måste vara kvinnorna, de starka och hårdbarkade, för nu höjer vi sakta hakan.” En skälvning i överkroppen med ben som längtar efter att spricka. En man lånar mina stämband innan han, med tätt ihopbundna handleder, släpas ner i det iskalla vattnet.Tanja Andersson

Ola Stinnerbom

Ola Stinnerbom is a contemporary choreographer, dancer and jojk singer who lives in Gothenburg. His family is also from the area around Saxnäs. In his work, he is researching forgotten Sámi dances, and he is also recreating Sámi drums. Together with Birgitta Stålnert, writer, filmmaker and a researcher of cultural studies, he runs Kompani Nomad. They want to change the image of what Sámi culture is and can be, with a particular focus on Sámi dance. They aim to show that Sámi dance existed, and to reinstate the Sámi dance tradition. Not in a strictly historical sense, but in a contemporary innovative form. Watch excerpts from ‘They call us Lap Ogres’:

All of these amazing artists show how they are able to combine activism and arts practices, and thus help change the discourse on Sámi identity and self-image. With their work they are involved in an international discussion on the major political changes caused by migration, nationalism, and debates on ethnicity. The Sámi artists are at the heart of the issues, which the art world today is very interested in.

My own connection to Saxnäs

I am not Sámi, and my family is not from Sápmi or from northern Sweden. Instead, I am the great grandchild of a failed immigrant from the southern part of Sweden, Småland. The further you were form the centres of power, the easier it was to be regarded as degenerate or lowly, this was also the case for southern Sweden. My great grandmother Viktoria left Sweden at a time when many Swedes emigrated to seek a new life in North America. Her siblings stayed in the U.S., but Viktoria returned by herself, and it is unclear why she came back. There has been a lot of silence and hidden trauma in my own family, indeed caused by the ideas of the pure race, and this is why I also relate on a personal level to many of the problems that young Sámi people are bringing to the surface. I will work with this trauma for my next performance ‘The Crone/Yamanba’.

Lars Dahlstedt 1855-1915

My connection to this place is through the artist-in-residence at Ricklundgården, and through my husband’s great-great grandfather Lars Dahlstedt. He was a priest in Vilhelmina and Fatmomakke. Lars was a prolific amateur photographer who depicted the life in Sápmi. You can find his photos in the Fatmomakke museum, in Vilhelmina and Umeå museum, and in many journals and books. Lars was also very interested in technical development, and could be seen biking around on a high wheel bicycle. He would always bring the bellows camera. About one hundred years after his death his great great grand child Palle Dahlstedt is looking at photography as a tool for artistic research and musical composition.

Snowflakes on the stairs of Ricklundgården 2017 Photo: Palle Dahlstedt

A Sámi wedding in Fatmomakke 1890 Photo: Lars Dahlstedt

The Fatmomakke parish in front of the new church 1899 Photo: Lars Dahlstedt

The Sámi religion was destroyed and abolished in the 18th century by the Swedish Church, and during Lars’ time as a priest most Sámi had become Christian. The Fatmomakke parish asked Lars Dahlstedt for a bigger church since the old one was too small. The new church was built collaboratively by Sámi and settlers in 1899, a decision made by Lars Dahlstedt. Kjellström writes about how this was a time of amity and neighborliness between settlers and the Sámi. Older Sámi who were not strong enough for the nomadic life could stay with a settler family in exchange for a reindeer. It was common for Sámi to stay overnight with the settlers on their hikes, often with the same families. Then gifts, stories and news were exchanged and this was widely appreciated. You learned from each other, and began to embrace each other’s routines and habits. The church weekends in Fatmomakke were highly appreciated by both Sámi and settlers and an opportunity for young people to meet. However, this was a time when religiosity was characterized by fear of God’s punishment. As late as 2001, the Church of Sweden acknowledged its injustices and asked the Sámi people for forgiveness.

Now I will write something about my own residency experience at the beautiful museum home Ricklundgården.

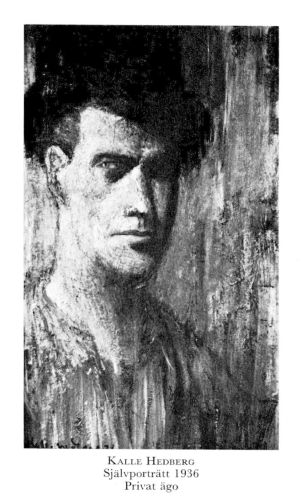

Kalle Hedberg

I have not met that many ghosts in my life, but when I stayed alone at Ricklundgården for two weeks in February, I got really frightened now and then. I heard footsteps, and doors closing and opening. This did not happen during my residency (with Heidi S Durning and Dianne Reid) in 2009.

I started to talk politely to Emma Ricklund and Lisa Stämp. Maybe they did not want me to be there? I have always felt comfort and hope thinking about these two strong women who worked hard to make Ricklundgården a welcoming home. Emma, who struggled to reassure her house would remain a guest home even after her death. No, I was pretty sure that they both wanted me there. I talked and sang to them. The portrait of Lisa Stämp, by Kalle Hedberg, is one of my favorite paintings. Here I walk slowly next to portraits of Emma and Lisa:

Ricklundgården is over seventy years old and the sounds of the house could indeed be explained rationally, but I was too exhausted from too much work, and I really felt ill at ease. I hardly could sleep at nights. Some guest artists who have had residencies before me, like Kjersti Dahlstedt and Katarina Pirak Sikku, confirmed the ‘ghost activity’ in the museum. Gerd Ulander finally suggested that it might be the (deceased) artist Kalle Hedberg. I discussed the matter with the artist Linnéa Carlsson who also held a residency in the annex. She was very moved by my ghost talks, and one night she made a sculpture and asked me: ”Is it him?”

Sculpture by Linnèa Carlsson

And yes, it must be him. Hello Kalle Hedberg!

Self-portrait by Kalle Hedberg

Emma Ricklund was an important artistic mentor for Kalle Hedberg. Maybe Emma wanted me to be introduced to his art? Or maybe Kalle Hedberg wanted to introduce himself? I found him a bit frigthening. Here I walk next to Kalle Hedberg’s 1930 portrait of Folke Ricklund:

I found his artistic statement, and it was not very encouraging for the state I was in:

‘Talent means nothing, but the desire, the excitement is of greater value, and to struggle with the problems. The joy is to see an artist struggling and falling, instead of walking in a line with a lazy bunch. Black is the stamp of mourning, but white can open worlds, where ideas go dizzy. Art has no color. Green to yellow can coalesce, become harmonies, as well as doctrines, black and white can be as much heaven as hell. The excitement. The intensity. The unresting hell.’

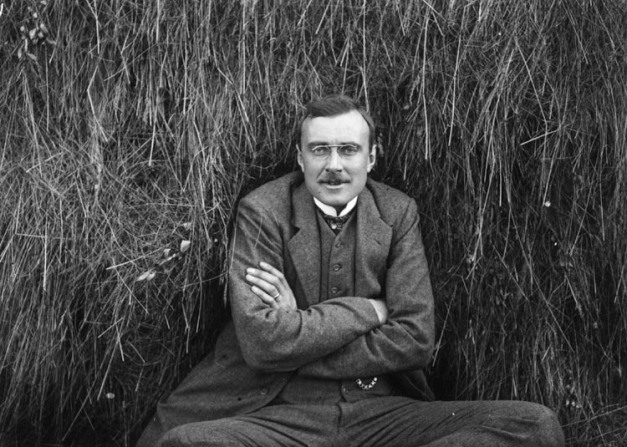

I decided to look further. After some research, I found out that Kalle Hedberg not only was a close friend to Emma and Folke Ricklund, but also to Helge Dahlstedt – the son of Lars Dahlstedt. Helge Dahlstedt is my husband’s great grandfather, and it is in his wonderful cabin in Bångnäs that we still stay each summer (without electricty and water – we have to chop woods, fetch water in a creek, cook on open fire).

I found a photo of him. I see my son’s features in him. Hello Helge Dahlstedt!

Helge Dahlstedt 1885-1963

Helge Dahlstedt and his wife Eva were both practicing doctors and artlovers. Since they worked in a time before advanced medication, art was also used in therapeutic ways to heal their patients. They believed in the social responsibility of medical science and the healing power of art. Their patients, suffering from tubercolosis, at Österåsens Sanatorium in Sollefteå were surrounded by art, and artists loved to spend time there, and were offered commissioned work to decorate the hospital. Poor artists were able to pay for their stay with paintings. Helge and Eva spend a lot of time at Ricklundgården with Emma, Lisa and Folke. I also found texts where Helge wrote warmly about Sámi citizens, and he confirmed that ‘Sámi people have through time been mistreated by us Swedes’. In his book Norrland i Konsten ((the North in Art), based on a lecture he gave in 1954, he defended the Swedish artist Johan Tirén, an artist who fought for the rights of the Sámi people, for depicting the hardships of the Sámi people in a time when some people claimed that noone was interested in this kind of art any longer. Helge confirmed that the art by Johan Tirén aroused the Swede’s guilt conscience; for example paintings like ‘Thief shots of reindeer’, and this painting of a mother with her son dead in a snowstorm:

Excerpt from Helge Dahlstedt’s book Norrland i Konsten (the North in Art)

Finding these stories about the past, and understanding connections between these people, and between the Sámi and the settlers finally helped me deal with the ‘ghost activity’ in the museum. I was also lucky to have the other guest artist, Linnéa, to talk to, and I was invited to listen to jazz with Gerd and her husband Lars-Göran Ulander. I was skiing everyday, and I continued my durational arts practice with walking slowly in suriashi:

This time also on ski:

Suriashi is a walk in which you relate to your past and to your ancestors. After all the years (since 2000) I have practiced this walk with or without my teacher Nishikawa Senrei, I will finally relate to my maternal ancestors.

I was invited to an excursion to Fiskonfjäll on snow mobiles with Saara Hermannson and her beautiful parents Joel and Laila. We performed suriashi together next to their cabin:

Finally, all the international participants arrived, and the Nordic Summer University’s first winter symposium in Sápmi began, and it became a very succesfull and memorable one for all of us. Now as I am here again, I realize that the participants of the Circle 7 also have become a part of the ‘ghostly activity’ in this museum. Hello Circle 7!

Saara Hermansson with Circle 7 in Folke Ricklund’s atelier Photo: Marina Velez

Circle 7 listening to philosophy and embroidering in the snow outside Ricklundgården 2017

In a presentation by Christine Fentz and Ragnhild Freng Dale, the contemporary Sámi film director Pauliina Feodoroff was quoted, in which she asks us not to flatter the landscape, something that deeply affected all of us. Indeed, this space is not a place for you to rest and to consume silence. It is not a postcard to be send out in the world. Saxnäs, Marsfjäll is a place where people live and work. Welcome the sound of snow mobiles as this sound shows the life in this village. Walk slowly, lean back, and relate to your ancestors. And have a happy new year.

Happy New Year 2018!!

P.S. On Feb 11th, I received an e-mail from Katarina Pirak Sikku. She writes that she was inspired by this blog post, and that she applied for a residency again at Ricklundgården. She wrote to me from the Folke atelier. She is making a hommage to her grandmothers who were originally from Kultsjödalen, the area between Saxnäs and Fatmomakke. Her grandmother was the neighbour of Lisa Stämps family. Katarina just came back from Östersund, from the 100th anniversary Sámi land meeting. In Östersund, she had met Eric-Oscar Oscarsson. He told her about the Nomad Schools that at first were organized through the Swedish church. However, there were some who did not want the Nomad school in their parishes. They thought that these Nomad schools were inhumane, and that many were treated in a bad way. Eric-Oscar Oscarsson told Katarina that there were two priests who opposed the prevailing system. One of the priests was a Dahlstedt in Vilhelmina.

This information was welcome, since I have wondered a lot about the position of Lars Dahlstedt in this time and space. I see his early 20th century opposition to the prevailing system as a healthy reminder that his attitude is something to acknowledge and replay. It might feel impossible in your own time and place, especially if your viewpoint represents a minority. But your actions will always have an impact for those who come after. No action is too small.